LAW SCHOOL TIMELINE

1812

University of Maryland faculty of law authorized by General Assembly

1824

Maryland Law Institute opens on South St. in Baltimore with six students and David Hoffman as dean

1833

Move to Courtland St.

1836

1836-1868

1869

1871

1879

1887

1891

1920

1925

1930

1931

1936

1938

1965

1968

1969

1971

1973

1976

1980

1984

1985

1987

1988

1989

1992

1997

1999

2001

2002

2004

2005

2008

2011

2014

2015

2018

2020

2022

2023

CELEBRATING 200 YEARS OF BOLD LEADERSHIP

by Wanda Haskel

by Wanda Haskel

In 2024, the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law—the fourth oldest law school in the country—marks 200 years since opening its doors as the Maryland Law Institute in 1824. In the following pages dedicated to this milestone, we highlight some select moments representing our enduring commitment to excellence in education, scholarship, and public service; groundbreaking work on the integration of theory and practice; and movement toward a more inclusive society within and beyond our walls. A complete history of the school’s bold leadership would be impossible to recount in this space. Instead, our hope is to offer readers a sense of the institution’s demonstrated commitment to transcendent innovation in legal education.

ONE OF THE FIRST LAW SCHOOLS IN THE NATION

In the early decades of the 19th century, the United States was in its infancy, with borders yet to be cemented and a system of government many considered experimental. Immature, too, was American legal education, which largely consisted of apprenticeships and “reading law” independently.

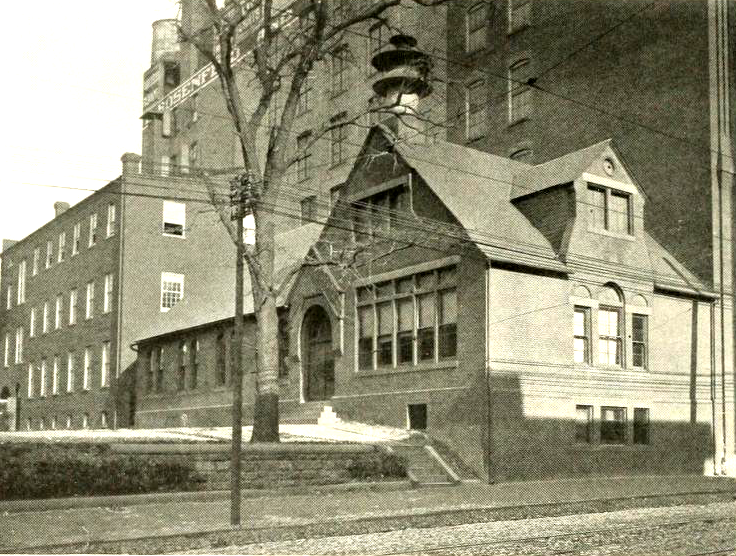

As demand for legal services in the young nation increased, universities began adding law faculty. The same year the British attacked Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, 1814, the University of Maryland hired its first professor of law—prominent Maryland bar member David Hoffman. One of the first in the country to pen a curriculum and lectures for “law learning,” Hoffman went on to be the founding dean (1823-1836) of the Maryland Law Institute, which opened for regular evening instruction on Baltimore’s South St. in 1824. The institute is considered the fourth oldest law school in the United States. By 1831, the student body had grown to around 30, and the Maryland Law Institute moved to Courtland St. in 1833 to be closer to the courts. Moot court opportunities from the earliest days of instruction set a course for the school’s long history of leadership in the integration of theory and practice.

Reflecting its association with the university, the institute was renamed the University of Maryland, Department of Law in 1836 but temporarily shut down the same year until after the Civil War when it was reestablished as the University of Maryland, School of Law in 1869. Ten years later, the student body had grown to 60 and the faculty was made up of a who’s who of Maryland’s bench and bar with former Maryland Attorney General John Prentiss Poe (second cousin to Edgar Allan Poe) as dean (1871-1909). In the late 1800s, the course of study went from a one- or two-year program to a required minimum of two years, illustrating the increasing stature of the legal profession and the expansion and complexity of discrete areas of the law.

Westminster Hall, adjacent to the law school, was built as a church in 1852. Its cemetery is the resting place of author Edgar Allan Poe and many other historical figures, including Founding Father James McHenry. In 1977, law school administrators led the establishment of the Westminster Historic Preservation Trust, which raised money to refurbish the hall in 1983. When the new law school building was constructed in 2002, Westminster was physically attached to Maryland Carey Law and now serves as a gathering place for law school and private functions.

.jpg)

CONFRONTING THE PAST

Notwithstanding the increased professionalization of legal education, the doors of the law school remained closed to everyone but White men until the second decade of the 20th century. The initial expansion was offered to White women who were allowed to enroll in 1920, with the first graduates in 1923. Black Americans and other people of color would have to wait longer for access.

In 1925, the academic program expanded to include a day program to comply with American Bar Association standards. Enrollment continued to rise and in 1931, the law school moved to a newly constructed three-story building with a library wing on the southeast corner of Redwood and Greene streets.

It would take another five years before anyone other than White people could take classes in the building. While the school allowed Black men to enroll in the aftermath of the Civil War, that practice was extinguished in the 1890s when Poe, now infamous for authoring legislation designed to disenfranchise Black voters in Maryland, was instrumental in resegregating the school with the backing of a petition from White law students. Finally, in 1936, Donald Gaines Murray ’38 was admitted, thanks to the tenacity of then-civil rights lawyer Thurgood Marshall, who, had he applied, would also have been denied admission because of his race. As Murray’s lawyer, Marshall successfully challenged Maryland’s practice of segregation in higher education in the landmark case Pearson et al. v. Murray. That same year, the Maryland Law Review, the only law journal in the state at the time, began publication.

Black graduates: Harry Sythe Cummings 1889, Charles W. Johnson 1889, and Donald Gaines Murray ’38 (second integration)

White women graduates: B. Olive Cole ’23, Ida Clare Lutzky ’23, Marie White Presstman ’23, Fannie Kurland ’23, and Helen I. Sherry ’23

Founder of an all-women law firm in Maryland: Rose Zetzer ’25

Founder of an all-Black law firm in Maryland, Brown, Allen, & Watts; and Black judge appointed to the Municipal Court in Baltimore City: Robert B. Watts ’49

Black man elected to the Maryland Senate and to sit on the Maryland Court of Appeals: Harry Cole ’49

Black women graduates: Dr. Elaine Carsley Davis ’50 and Juanita Jackson Mitchell ’50, who became the first Black woman to practice law in Maryland

Asian American graduate: Frank Chuman ’45

White woman faculty member: Alice Brumbaugh, 1969

Black man tenured full professor: Larry Gibson, 1974

Black woman appointed to the Maryland District Court: Mabel Hubbard ’75

Latino appointed to the Maryland District Court: Ricardo Zwaig ’82

Woman general counsel on Wall Street: Christine Edwards ’83

Woman chief judge, Maryland Supreme Court: Mary Ellen Barbera ’84

Black woman tenured full professor: Taunya Lovell Banks, 1989

Woman dean: Karen Rothenberg, 1999

Black dean: Phoebe Haddon, 2009

PROGRESS

PROGRESS

The years to come would bring increased access to the legal academy for those who had previously been excluded. In 1946 Black women were allowed to enroll as law students, and in 1969 the first White woman joined the faculty. It would be another two decades before the first Black woman faculty member gained tenure status in 1989.

The law school moved locations again in 1965, when a new law school building was completed at Baltimore and Paca streets. The space accommodated around 550 students, 11 full-time faculty, and 50,000 library volumes. Chief Justice Earl Warren was the guest-of-honor at the opening celebration.

Charged by the Civil Rights and Women’s Rights movements, the student body and faculty began to diversify in earnest during the next decade, with the founding of the Black Law Students Association in 1968, the hiring of more faculty focused on civil rights, and a dramatic up-tick in women applying to law school.

Just before the new millennium, the first woman dean, Professor Emeritus Karen Rothenberg (1999-2009), was appointed. Soon after, the law school moved into today’s modern law school building, with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg offering the keynote address at the dedication. Professor Donald Gifford is credited with the initiation and much of the funding outreach for the new structure during his deanship (1992-1999). Rothenberg also secured funding, ensured that high-tech classrooms and reasonable accommodations were baked into the design, and completed the project.

Following the first woman dean was the first Black dean, Phoebe Haddon (2009-2014), and, in 2011, in recognition of a $30 million transformative gift from the W. P. Carey Foundation, the law school adopted its current name, the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law or Maryland Carey Law. The appellation honors Francis King Carey, an

1880 graduate and prominent founding member of two major Baltimore law firms.

MARSHALLING EXCELLENCE TO INCREASE IMPACT

As early as the 1930s, law school students gained clinical experience working at the Baltimore Legal Aid Bureau. But under the leadership of Dean Michael Kelly (1975-1991), opportunities for students to apply, in a real-world practice setting, the legal theory they were learning in class multiplied and became one of the law school’s hallmarks. By the early 1970s, the school had a formal externship program with the Legal Aid Bureau and a grant-funded, in-house Juvenile Law Clinic. Other early clinics addressed legal issues around jail reform and civil rights, disability rights, housing, health, elder law, bankruptcy, consumer protection, environmental law, mediation, and AIDS.

As early as the 1930s, law school students gained clinical experience working at the Baltimore Legal Aid Bureau. But under the leadership of Dean Michael Kelly (1975-1991), opportunities for students to apply, in a real-world practice setting, the legal theory they were learning in class multiplied and became one of the law school’s hallmarks. By the early 1970s, the school had a formal externship program with the Legal Aid Bureau and a grant-funded, in-house Juvenile Law Clinic. Other early clinics addressed legal issues around jail reform and civil rights, disability rights, housing, health, elder law, bankruptcy, consumer protection, environmental law, mediation, and AIDS.

A pivotal moment in the Clinical Law Program’s history came in 1987 when then-U.S. Representative Ben Cardin ’67 and others led the charge for the Maryland General Assembly to allocate funds to expand the program and establish a Legal Theory and Practice component, which dramatically increased clinical options for students. The law school was one of the earliest adopters of clinic participation as a requirement for graduation, which became known as the “Cardin Requirement” in Maryland Carey Law’s curriculum. Now, many law schools across the country have followed suit.

The state funds enabled even more growth in the decades to follow with the launch or reinvigoration of clinics in areas including immigration, public health, tax, mediation, gender violence, juvenile justice, criminal appeals, post-conviction and sentencing, reentry, and intellectual property. Others in the last five years alone include criminal defense, survivors of violence, appeals immigration, and eviction prevention.

Today, students, under faculty supervision, provide around 75,000 hours (or about eight and a half years’ worth) of free legal services to disadvantaged and underrepresented communities in 17 clinics every year.

Along with a significant expansion of the Clinical Law Program in the 1980s and 1990s, the law school began offering specialized academic programs, many incorporating clinics, and some with the opportunity to earn a certificate.

Foreseeing the need for specialized legal expertise in the emerging field of health law, in 1984 the law school established the Law & Health Care Program, a perfect fit for a law school located on a health sciences campus as well as close to several federal health regulatory agencies. Early on, faculty in the program addressed issues such as end of life care, genetic testing, and access to emergency care. Soon thereafter, the pioneering Environmental Law Program was established in 1985. Its founding coincided with a rising awareness of the effects of pollution and climate change and anticipated the explosion in demand for lawyers trained in environmental law.

Maryland Carey Law clinics constantly develop and evolve to meet longstanding and emerging needs. Approximately 17 clinics are offered every year. They include:

- Consumer Bankruptcy

- Consumer Protection

- Criminal Appellate

- Criminal Defense

- Environmental Law

- Eviction Prevention

- Fair Housing

- Federal Appellate Immigration

- Gender, Prison, and Trauma

- Immigration

- Intellectual Property and Entrepreneurship

- Low-Income Taxpayer

- Mediation

- Medical-Legal Partnership

- Public Health

- Survivors of Violence

- Youth, Education, and Justice

In 200 years, the law school library has grown from a few foundational tomes to today’s four floors, featuring over 400,000 volumes of legal materials, access to hundreds of legal databases and online journals, and borrowing privileges among 17 Maryland libraries.

In 200 years, the law school library has grown from a few foundational tomes to today’s four floors, featuring over 400,000 volumes of legal materials, access to hundreds of legal databases and online journals, and borrowing privileges among 17 Maryland libraries.

In 1980, the current library’s initial construction on Paca St. was completed and named in honor of the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. In 1982, the law school automated the library catalog and later launched Digital Commons, a repository to showcase the full range of scholarship produced at the law school. Today, the library is the research and technology hub of Maryland Carey Law.

Multiple new programs and centers emerged during Rothenberg’s deanship in the 2000s, including one of Maryland Carey Law’s most innovative academic programs, the Women, Leadership & Equality Program, founded in 2002. The program provides a trailblazing curriculum that examines the structural barriers keeping women from ascending to positions of leadership in the legal profession. It equips students with the knowledge and skills to overcome and dismantle those barriers. At inception, the program was the first and only of its kind in the country.

Multiple new programs and centers emerged during Rothenberg’s deanship in the 2000s, including one of Maryland Carey Law’s most innovative academic programs, the Women, Leadership & Equality Program, founded in 2002. The program provides a trailblazing curriculum that examines the structural barriers keeping women from ascending to positions of leadership in the legal profession. It equips students with the knowledge and skills to overcome and dismantle those barriers. At inception, the program was the first and only of its kind in the country.

The year 2002 also saw the founding of two high-impact centers: the Center for Dispute Resolution (C-DRUM) and the Center for Health and Homeland Security (CHHS).

The Center for Dispute Resolution trains students to navigate conflicts and solve problems in constructive ways and is a leader in developing and improving the quality of dispute resolution processes in Maryland’s courts, schools, workplaces, and communities. C-DRUM offers an academic track in dispute resolution, houses the Mediation Clinic, and trains Maryland public school educators and policymakers across the state in conflict resolution.

The University of Maryland Center for Health and Homeland Security houses a staff of more than 40 lawyers who work with emergency responders around the globe to develop plans, policies, and strategies for government, corporate, and institutional clients in the areas of emergency preparedness and crisis response. CHHS staff also teach in Maryland Carey Law’s Cybersecurity and Crisis Management Program in which law students specialize and gain experience as externs at the center.

Additionally, in the early 2000s, the law school launched the Legal Resource Center for Public Health Policy, providing technical legal assistance to Maryland state and local health officials, legislators, and organizations working in tobacco control. That work expanded dramatically, and in 2010, Maryland Carey Law became the home of the Network for Public Health Law-Eastern Region, which provides technical legal assistance to national, state, and local public health professionals, attorneys, legislators, and advocates working to develop sound public policy to improve public health.

In the late 1980s through the ’90s, the Business Law and Intellectual Property Law programs were also beginning to take shape, with the official founding of both in the early 2000s and a significant expansion of the Business Law Program in 2011 thanks to the transformative W. P. Carey Foundation gift. The Maryland Intellectual Property Legal Resource Center was founded in 2002 and laid the foundation for what would eventually become the Intellectual Property and Entrepreneurship Clinic in 2018.

To meet the demand for globally competent legal professionals, the law school in 2008 established the International and Comparative Law Program, which helps students understand the social, cultural, political, and economic factors that influence how the law is applied and offers study abroad opportunities in countries including Malawi and Ireland.

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE

With eyes toward the future, many of the law school’s recent efforts have focused on harnessing expertise and advocacy to expand community outreach and deepen work addressing society’s systemic inequities.

Under the leadership of Professor Donald Tobin during his deanship (2014-2022), the law school launched multiple new clinics, the Levitas Initiative for Sexual Violence Prevention, and, thanks to a transformative gift from Dr. Marco and Debbie Chacón, the Chacón Center for Immigrant Justice. The center, which builds on the expertise in Maryland Carey Law’s long-running Immigration Clinic also includes a new Federal Appellate Clinic, which gives students additional opportunities to work directly with clients and advocate for law reform and policies to fundamentally improve the immigration system.

This year the law school launched the Gibson-Banks Center for Race and the Law, which works to reimagine institutions and transform systems of racial and intersectional inequality, marginalization, and oppression. The center represents the law school’s vision and leadership in helping Maryland be a national model of re-envisioning systems and institutions to protect and improve the lives of everyone.

CHANGE MAKERS

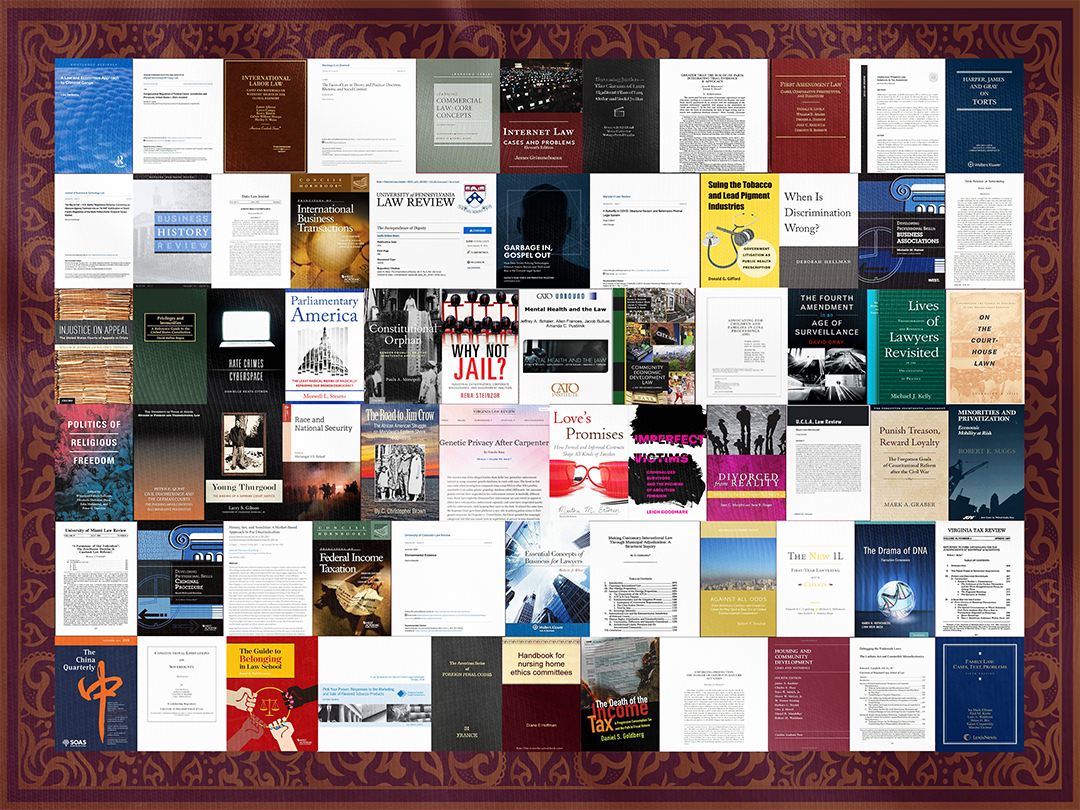

Essential to the deep tradition of combining theory and practice is a commitment to nurturing a faculty made up of thought leaders. Since the days when founding Dean David Hoffman “wrote the book” on the curriculum for American legal education, law school scholars have been foundational thinkers and trailblazers in areas including business law, civil and political rights law, constitutional law, criminal law, cybersecurity, dispute resolution, environmental law, gender and family law, health law, housing law, immigration and human rights law, intellectual property, international law, and legal pedagogy. Their work is published in books, esteemed academic journals, and major newspapers.

Faculty are invited to present at conferences hosted by top universities around the world and are called upon by local and national media outlets to share expertise on an array of legal issues. Through their connections and partnerships with regional, national, and international thinkers, Maryland Carey Law faculty convene conferences, talks, panels, symposia, and workshops at the school that attract star scholars and practitioners from far and wide and enrich the intellectual life of the Maryland Carey Law community.

As a top law school and a Maryland fixture for 200 years, Maryland Carey Law has graduated thousands of students who have gone on to be legal leaders in private practice, the judiciary, government, public interest, and business. Alumni are U.S. senators, house representatives, and attorneys general. In Maryland, the school’s alumni have served as governors, senate presidents, legislators, county executives, Baltimore mayors, and chief legal counsel to elected officials at all levels of government. Graduates are judges and chief judges in federal and state courts. They are founders and partners of the most influential law firms in Maryland, solo practitioners, and real estate developers. They are in-house counsel and executives for major business concerns, sports organizations, and non-profits. And the law school has trained an army of social justice warriors, who found and lead a range of legal aid organizations and public interest law firms and have championed the rights of underserved populations and everyday Marylanders by building pro bono programs, serving as public defenders and prosecutors, and entering public service.

THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

This “tapestry” offers just a sampling of influential scholarship by law school faculty.

Maryland Carey Law has always nurtured robust legislative advocacy. Efforts by faculty and students have been key to policy reforms and the passage of and compliance with legislation aimed at creating more just and equitable law and policy in Maryland and beyond. Some examples are:

- Prohibition of smoking in indoor spaces

- Raising the age of lawful access to tobacco products to 21

- Establishment of restorative approaches in Maryland schools

- Right to counsel at eviction proceedings

- Closing of the infamous state-run Montrose School

- Abolition of the death penalty

- Improvements in conditions at the Baltimore City Jail

- Removal of the governor from the parole process

- Prevention of illegal seizures on Maryland light rail

- Restrictions on police use of commercial DNA databases in criminal investigations

- Probation Before Judgment reform giving noncitizens access to probation in Maryland without the risk of deportation

- Cannabis Reform Act

- Child Victim’s Act

- Maryland Mediation Confidentiality Act

- Maryland Health Care Decisions Act

- Reduction of Lead Risk in Housing

- Anti-revenge-porn legislation

- Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act

- Overdose Response Program Act

- Multiple pieces of legislation improving conditions for children in foster care and promoting expeditious reunions with biological families and adoptions

CAREY FORWARD

CAREY FORWARD

Reckoning with the exclusionary aspects of our past helps us appreciate the progress we have made and informs us as we set a course for our future. These days we are proud that our student body typically comprises over 35% underrepresented minorities and exceeds 50% women. The faculty is also half women. A recent national study looking at the progress of women’s representation and achievement in American law schools between 1948 and 2021 found that Maryland Carey Law placed historically first for women’s representation among faculty and second for students.

We view diversity in the legal profession as an imperative. In the wake of the recent Supreme Court decision on affirmative action, we remain committed to advancing diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging in legal education and in the legal profession using the lawful tools available to us. Lawyers from diverse backgrounds bring unique perspectives and cultural insights that enrich the legal system, encourage innovation, and better serve clients from all walks of life. Presently, the legal profession falls far behind other professions in reflecting the diversity of the general population. We believe it is our responsibility to ensure we are educating the next generation of lawyers with an eye toward closing that gap.

Dean Renée McDonald Hutchins, appointed in 2022, ushers in an era with increased emphasis, through scholarship and advocacy, on interrogating and reimagining the systems that perpetuate society’s inequalities. The start of Hutchins’s tenure also heralded a renewal of our long dedication to nurturing a law school community, including 13,000-plus alumni, that prioritizes excellence in a welcoming and caring atmosphere. In the current climate, that means finding new ways to support students’ overall wellness as they face the mental health crisis that plagues our population. As the dean told this year’s incoming class, “We are a family.”

Dean Renée McDonald Hutchins, appointed in 2022, ushers in an era with increased emphasis, through scholarship and advocacy, on interrogating and reimagining the systems that perpetuate society’s inequalities. The start of Hutchins’s tenure also heralded a renewal of our long dedication to nurturing a law school community, including 13,000-plus alumni, that prioritizes excellence in a welcoming and caring atmosphere. In the current climate, that means finding new ways to support students’ overall wellness as they face the mental health crisis that plagues our population. As the dean told this year’s incoming class, “We are a family.”

And we are a family coming together with a vision. We are Maryland’s flagship law school, home to leading scholars and change-makers. We are preparing the next generation of lawyers to lead with compassion and protect the rights of all people equally under the law, to use their access and power to build the American ideal that we still haven’t realized, and to craft policy that inch by inch will make our country a more perfect union.